Visitors to St. Paul’s downtown area are often captivated by the visual grandeur of the city’s castle-like architectural crown jewel, Landmark Center. Few are aware, however, that the building’s colorful history is equally as impressive. As the saying goes, “if these walls could talk,” those in Landmark Center would have volumes to say about the events that occurred there years ago. [Go to photo gallery]

An Inspired Design

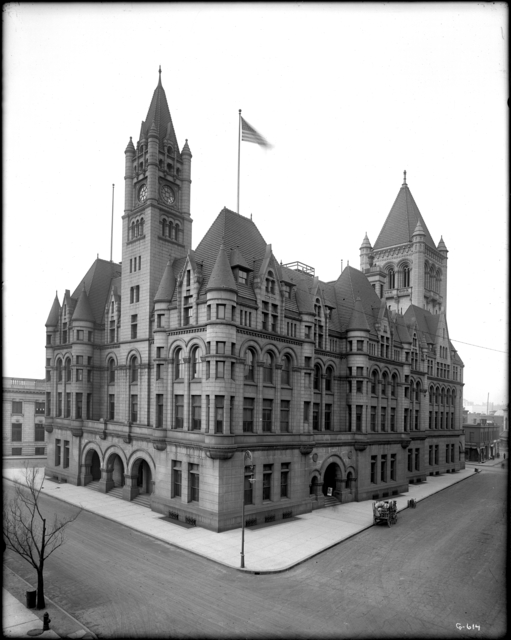

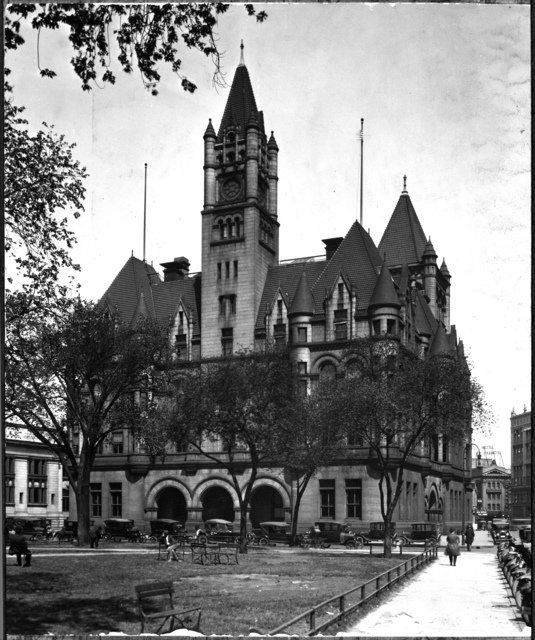

Located at the corner of Fifth and Market Streets in downtown St. Paul, Landmark Center was designed in 1892 as the Federal Courts Building by architect Willoughby J. Edbrooke. It was originally built to house the Federal Courts, Postal, and other government offices in the city.

Designed in the Richardsonian Romanesque style that was so popular in the mid to late 1800s, the building is among one of a number of similarly designed structures in the U.S. The others were built in Detroit, Omaha, Milwaukee and most notably, Washington D.C. Prominent local architects James Knox Taylor and Edward P. Bassford were also involved with the design of the building. Cass Gilbert, the architect of the Minnesota State Capitol, supervised part of its construction.

In February of 1891, the U.S. Congress approved $800,000 for the construction of the new Federal Courts Building in St. Paul and work began the following year. By 1898, it became clear that additional space was needed and Congress authorized an additional $700,000. Once completed, the Federal Courts Building cost $2.5 million, including furnishings.

Grand and Stately

Built on the site of St. Paul’s first city hall (1857-1891), Landmark Center features two prominent towers. The south clock tower along Fifth Street extends 167 feet above ground level to the top of its spire and was part of the original 1892 building design. The north tower along Sixth Street is a more massive structure featuring a 46-foot square base that rises 244 feet to the top of its spire. The north tower was added as part of the 1899 addition to the building and was modeled after the tower on Boston’s Trinity Church, which was designed by famous architect Henry Hobson Richardson.

The façade of Landmark Center is constructed of smooth St. Cloud granite and features a collection of gables, dentil cornicing, and arcades. Intricately carved grotesques, owls, and other artistic embellishments add a distinctive flair to the building’s exterior. The conical roofs of the tourelles outlining the footprint of the building are sheathed in patina-covered copper which contrasts with the red slate tiles of the structure’s main roof.

The centerpiece of Landmark Center’s interior is a four-story cortile bordered by ornate columns topped with Corinthian capitols. The walls in common areas and hallways are dressed with marble wainscoting. The four courtrooms in the building feature marble fireplaces, intricately carved mahogany woodwork, and elegant stained glass reminiscent of the Gilded Age of architecture.

A Distinctive History

Landmark Center’s history is a colorful one and includes notable personalities from both sides of the law.

Congressman Andrew Volstead maintained an office on the fifth floor of Landmark Center when he co-authored the 18th Amendment, also referred to as the Volstead Act, which created National Prohibition. Volstead served in Congress from 1903-1923 and was Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee from 1919 to 1923.

Warren Burger, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, tried his early cases in the building and Associate Justice Harry Blackmun began his career as a law clerk there. Both men grew up on the east side of St. Paul and today their portraits hang in Landmark Center’s Chief Justice Room (430).

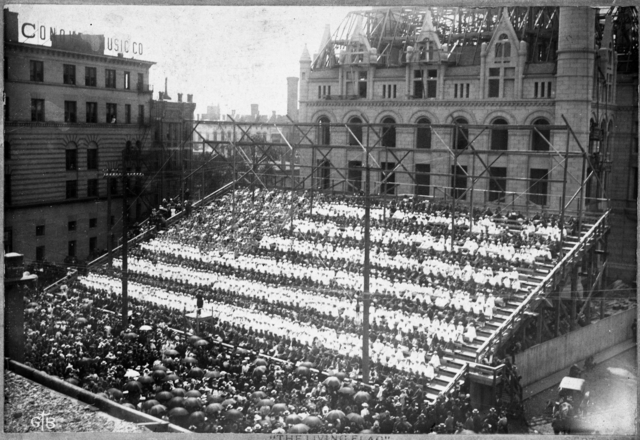

Presidents Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower both made campaign speeches from the balcony overlooking the Fifth Street entrance facing Rice Park. Incidentally, the only way for the them to access the balcony was to crawl through a window from the office behind it.

1930s Gangster Era

As a federal courthouse, Landmark Center was at the epicenter of the trials of some of the most notorious criminals of 1930s gangster era in the Twin Cities.

In May of 1934, Mary Evelyn “Billie” Frechette was brought to trial at Landmark Center for harboring known criminal John Dillinger, with whom she was involved romantically.

On March 31 of that year, Frechette and Dillinger were hiding out at the Lincoln Court Apartments in St. Paul when the two, along with known criminal Homer Van Meter, were involved in a dramatic shootout with two FBI agents and a local police detective. During the exchange of gunfire, Dillinger was wounded in the leg and escaped to the clinic of Dr. Clayton E. May in Minneapolis.

Frechette, along with Dr. May and his nurse Augusta Salt, was tried in Landmark Center’s Ramsey County Room (317). Frechette and May were convicted of harboring Dillinger and sentenced to two years in prison. Salt was acquitted.

Edward Bremer Kidnapping

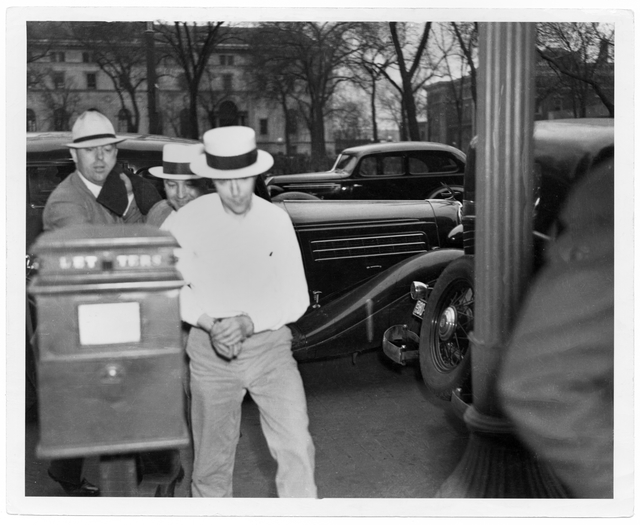

Known criminals Arthur ‘Doc’ Barker and Alvin “Creepy” Karpis were also tried in Landmark Center’s Room 317 for the kidnapping of banker Edward G. Bremer, Jr.

Bremer was kidnapped on his way to work on January 17, 1934. He had just dropped off his daughter at the Summit School in St. Paul when he was approached by two men. One of the men, later identified as Barker, repeatedly punched and pistol-whipped Bremer and then forced him into the back of a waiting car.

After having some difficulty starting the vehicle, the two men sped off with Bremer in the back seat, later switching to another car. Bremer was held captive in Bensenville, Illinois for the next three weeks, until February 7th when the kidnappers received a ransom of $200,000.

After the kidnapping, Barker was tracked down in Chicago and apprehended on January 13, 1935. At the conclusion of his criminal trial at Landmark Center on May 17th of that year, Barker was convicted of the kidnapping of Bremer and sentenced to life in prison at Alcatraz. Four years later, on January 13, 1939, Barker was shot and killed while trying to escape from the prison.

Karpis was arrested on May 1, 1936 in New Orleans, Louisiana and was taken into custody by none other than J. Edgar Hoover and his team of federal agents. He initially pled not guilty to the kidnapping of Bremer, but ultimately entered a guilty plea of conspiracy to commit the kidnapping. In a courtroom guarded by machine gun wielding federal agents, he was sentenced to life in prison and served his time in Alcatraz as well. Karpis became the prison’s longest serving inmate.

William A. Hamm, Jr. Kidnapping

In July 1936, Jack Peifer was tried for the kidnapping of William A. Hamm Jr., President of Hamm’s Brewing Company, in Landmark Center’s Room 317. Described as a fixer and gambler, Peifer owned the Hollyhocks Club situated on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River in St. Paul.

Hamm was kidnapped on June 15, 1933, by members of the Barker-Karpis gang, while walking home for lunch from his St. Paul office. He was approached by Charles Fitzgerald near the intersection of Greenbrier Street and Minnehaha Avenue East and forced to the ground. A waiting black sedan pulled up with Fred Barker and Alvin Karpis inside. Hamm was forced onto the floor of the back seat and was subsequently driven to Bensenville, Illinois where he was held until a $100,000 ransom was paid three days later.

Months before the kidnapping occurred, Peifer met with gang leaders Alvin Karpis and Fred Barker at his Hollyhocks Club and proposed his idea to kidnap Hamm. Peifer also arranged for a cottage north of St. Paul on Bald Eagle Lake where the conspirators planned the crime.

On July 31, 1936, Peifer was found guilty of conspiracy to commit kidnapping and was sentenced to 30 years in Leavenworth. As Judge Matthew M. Joyce denied his motion for a new trial and chastised him about his lawlessness, Peifer pulled a handkerchief containing a single capsule of potassium cyanide from his back pocket. He swallowed the pill and died two hours later in a Ramsey County jail cell.

A Forsaken Landmark

While Landmark Center’s history had been well preserved over the years, the structure itself was neglected and became dilapidated. Much of the building’s deterioration could be attributed to time and the elements while some was due to its caretakers.

The U.S. Post Office, which occupied the main floor of the building, painted over the marble walls with green #102-A paint – a cheap and common color used in government buildings at the time. Marble wainscoting was removed and replaced with mailboxes. A louvered, paneled ceiling was installed at the second floor level covering the main floor cortile.

Two of the beautiful features that allowed natural light into the building were covered up. The skylight over the cortile at the fourth floor was concealed in corrugated asbestos. And the beautiful stained glass skylight that adorned the law library was painted over on the inside.

False ceiling panels were added throughout the building and florescent lighting replaced the original fixtures designed to operate on both gas and electricity. The original marble mosaic floors were replaced with plain tile and the maple flooring was hidden under brown linoleum.

Outside the building, the original red clay tiles that covered the main roof were replaced with asphalt shingles and the pink hue of the St. Cloud granite façade was transformed to a dirty grey as a result of years of exposure to soot and grime.

Rescued

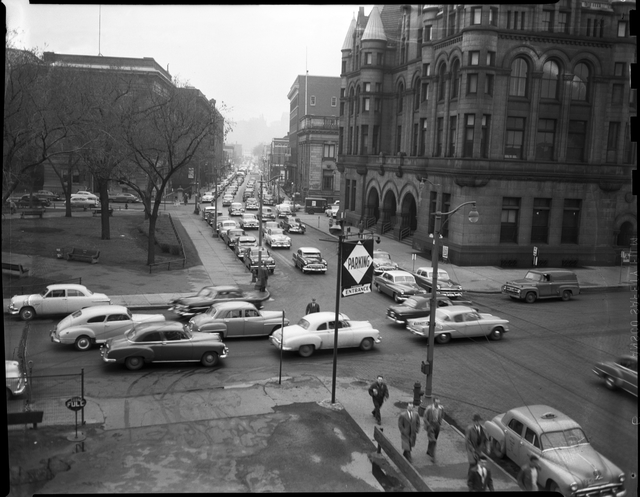

As the years passed, Landmark Center began showing its age more and more. Needing additional space, in 1961 the federal government began construction of a new Federal Courts Building on Kellogg Boulevard between Jackson and Robert Streets in St. Paul. By 1967, only a branch post office remained in Landmark Center.

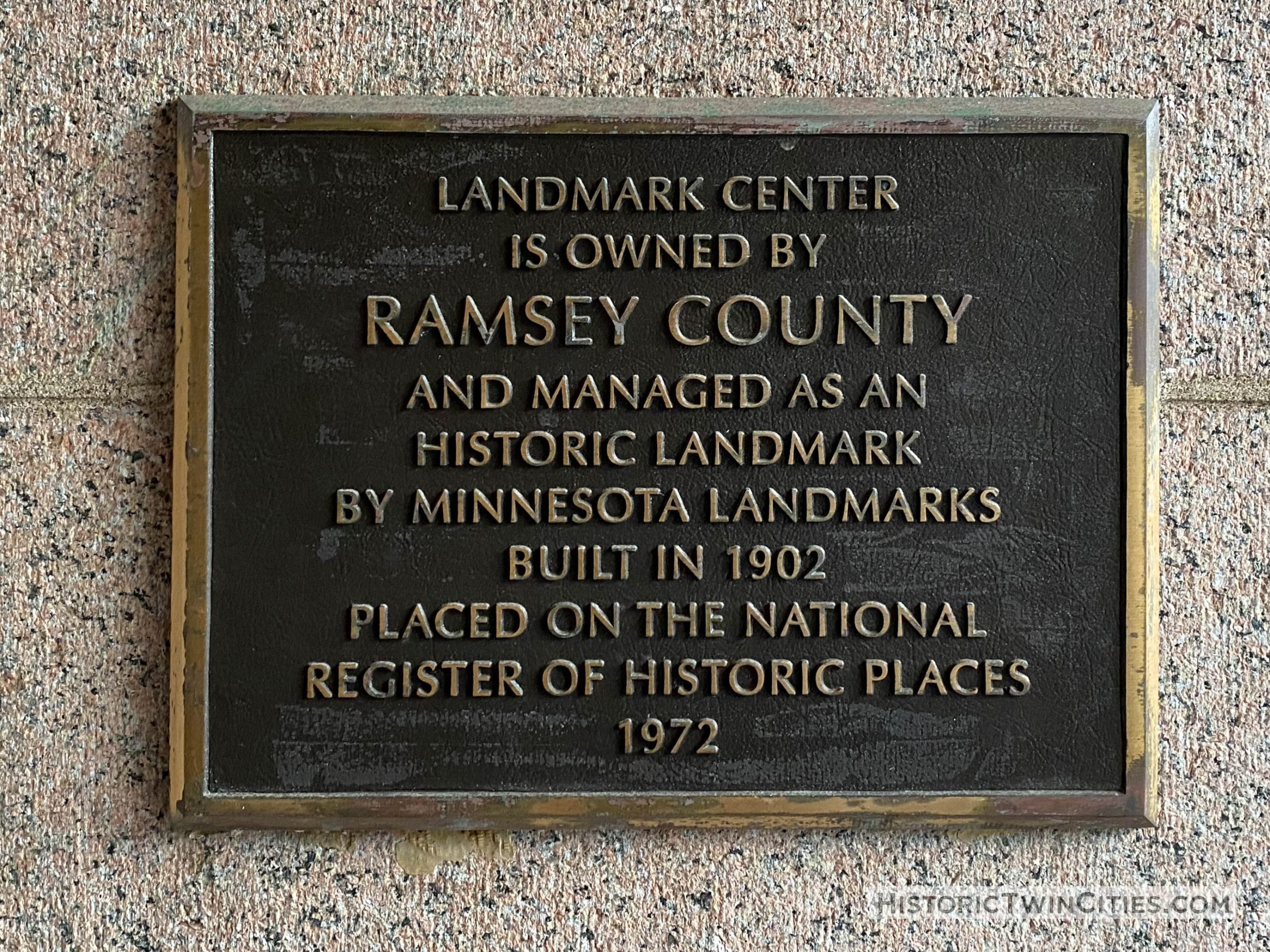

In 1968, at risk of losing Landmark Center to urban renewal and modernization, St. Paul Mayor Thomas Byrne formed the nine member “Mayor’s Committee to Preserve the Old Federal Building.” That committee was influential in the building’s early preservation and its eventual listing on the National Register of Historic Places as the “Old Federal Courts Building” on March 24, 1969.

Research and documentation for the building’s nomination to the National Register were prepared by Georgia Ray DeCoster. A member of the St. Paul Planning Board in the late 1960s, DeCoster was an advocate for historic preservation and a founding director of the Mayor’s committee that, in 1970, would become known as Minnesota Landmarks.

By the early 1970s the ground floor of Landmark Center was the only one occupied by tenants. Windows in the upper floors were broken, exposing the building to the elements, and pigeons roamed the halls. Pipes burst in the unheated upper floors and plaster walls crumbled.

Beautiful Once More

On October 20, 1972, the City of St. Paul purchased Landmark Center from the General Services Administration for $1. Under the direction of the committee formed by Mayor Byrne, now renamed Minnesota Landmarks, a restoration effort got underway to rehabilitate the old building. Newly elected St. Paul Mayor, Larry Cohen, became a key figure in the restoration project, as did St. Paul’s first City Administrator and former City Council member, Frank Marzitelli.

Over the next ten years, Landmark Center was transformed back into the beautiful castle that once graced the heart of St. Paul’s downtown.

The renovation effort, and fundraising that accompanied it,led by St. Paul community leader and philanthropist Elizabeth W. Musser,included three phases:

Phase One included repairing windows, removing the green paint from the marble wainscoting, scrubbing the years of dirt and grime from the granite exterior, and beginning the restoration of three of the building’s four courtrooms.

Phase Two of the project included new mechanical and electrical systems, removing the louvered ceiling over the main floor cortile, and removing the paint that covered the stained-glass ceiling in two of the courtrooms. Construction of a new auditorium located in the basement also began.

Phase Three saw the completion of the basement auditorium and restoration on the courtrooms and offices was finished.

In 1975, ownership of Landmark Center was transferred to Ramsey County and fundraising for its restoration effort began in earnest. Moving forward, the County would provide annual funds and maintenance for the building’s upkeep. Several members of the Ramsey County Board of Commissioners at that time would also go on to serve as directors on the Minnesota Landmarks Board.

On September 9, 1978, a grand opening for the public was held at Landmark Center attended by Vice President Walter Mondale and his wife, Joan. At this point, only the main floor of the building was completed. Work continued in the basement and upper floors over the next 4 years. Finally, in 1982, a “Finished at Last” celebration was held to mark the completion of the massive restoration effort.

Modern Usefulness

Today, Landmark Center is still owned by Ramsey County and continues to be operated by Minnesota Landmarks as an historic site and cultural gathering place. It hosts a full annual schedule of public programs, concerts and festivals, as well as private events. Organizations such as the Schubert Club Music Museum, the Ramsey County Historical Society, and the American Association of Woodturners – Gallery of Wood Art maintain spaces in the building as well.

Once the center of the 1930s underworld court drama, Landmark Center now sits at the cultural center of the city of St. Paul and acts as a reminder of the beauty and grandeur of St. Paul’s days gone by.

If you visit….

Landmark Center is located at 75 West Fifth Street in downtown St. Paul. The building is open to the public seven days a week and includes a staffed Visitor Information Center on the main floor.

Back to Top

Special thanks to the following people who provided help or information for this piece:

Amy Mino, Executive Director – Landmark Center

References:

- National Register of Historic Places – Inventory Nomination Form, ‘Old Federal Courts Building, St. Paul, Minnesota’ (3/24/1969)

- Young, Billie. (2002) Landmark – Stories of a Place, Minnesota Landmarks , Inc.

- Millett, Larry. (2007) AAA Guide to the Twin Cities, Minnesota Historical Society Press

- Frethem, Deborah & Schreiner, Cynthia. (2020) Alvin Karpis and the Barker Gang in Minnesota, The History Press

- Maccabee, Paul. (1995) John Dillinger Slept Here, Minnesota Historical Society Press

- Barker, 4 Other Guilty in Kidnapping in Bremer Kidnapping; 2 Freed , Minneapolis Star, May 17, 1935

- Peifer Dies of Poison Pill Taken as He Hears Term, Minneapolis Tribune, August 1, 1936

- Dillinger Girl and Doctor Convicted, Minneapolis Star, May 23, 1934

- Kidnap Wm. Hamm, Demand $100,000: Sankey Suspected, Minneapolis Star, June 17, 1933

- Curt Brown, St. Paul gangster’s kidnapping trial came to dramatic end, Minneapolis Star Tribune, April 3, 2021

- Landmark Center – A Work of Art Serving People, video Produced and Directed by Woody Mueller and Peter B. Myers

- St. Paul, Minnesota Landmark Center, HauntedHouses.com